“Modern technology is the worst thing that ever happened to the world, and to promote its progress is nothing short of criminal”.

These are the words of Ted Kaczynski, the subject and focus of Ted K, directed by Tony Stone. They are the words of a domestic terrorist who enacted a reign of terror between 1978 and 1995, killing 3 people and injuring 23 others; a man the world would come to know under the moniker of ‘The Unabomber’.

It’s Kaczynski’s own words that form the basis of the film’s dialogue as writers Gaddy Davis and John Rosenthal (along with Tony Stone) mined Kaczynski’s extensive collection of writings (25,000 pages in total) to help shape the film. Kaczynski’s own words are used not to justify his actions, or even provide fuel for empathy- there are many points in the film where viewers may find his more extreme opinions distasteful- instead, his words provide a path of progression from simply living off the grid in Montana to creating and sending explosive devices that were meant to kill their targets.

The film offers a slice of Kaczynski’s timeline. Instead of a winding biopic that goes from childhood onwards, Ted K captures his years in the wilderness leading up to his eventual incarceration. We are introduced to Ted (played by Sharlto Copley) watching snowmobiles criss-crossing snowy terrain dotted by fire-blackened trees. This is one convention the film uses effectively – Kaczynski as the constant observer, framing him as the sole witness to environmental destruction and industrial ruin.

He watches as the noxious orange smoke of herbicides waft into the air, the resultant herbicide dripping from berry bushes like blood. He looks on as logging equipment lifts their felled victims into the air. As a counterpoint, he comes face to face with a majestic mountain lion lazing on a tree branch. Kaczynski is also very much the outside observer when it comes to romantic relationships. A self-professed virgin, he has no respect for women and even calls his brother David “domesticated” for getting married.

In addition to having Kaczynski perceived as the sole observer to the damage of the environment, sound is used very effectively in Ted K to get even further into Kaczynski’s mindset and motivations for terrorism. The idyll of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons playing in Ted’s cabin and the gentle sounds of nature are battling with the sounds of progress: the hum and crackle of powerlines, the whine of a buzzsaw, the roar of a jet engine. All of these sounds help to ferment his rage.

At the highest end of Kaczynski’s spectrum for intolerance is the sound of a computer store in a city, as the cacophony of computer noises also compete with the garish neon lights to assault his senses completely.

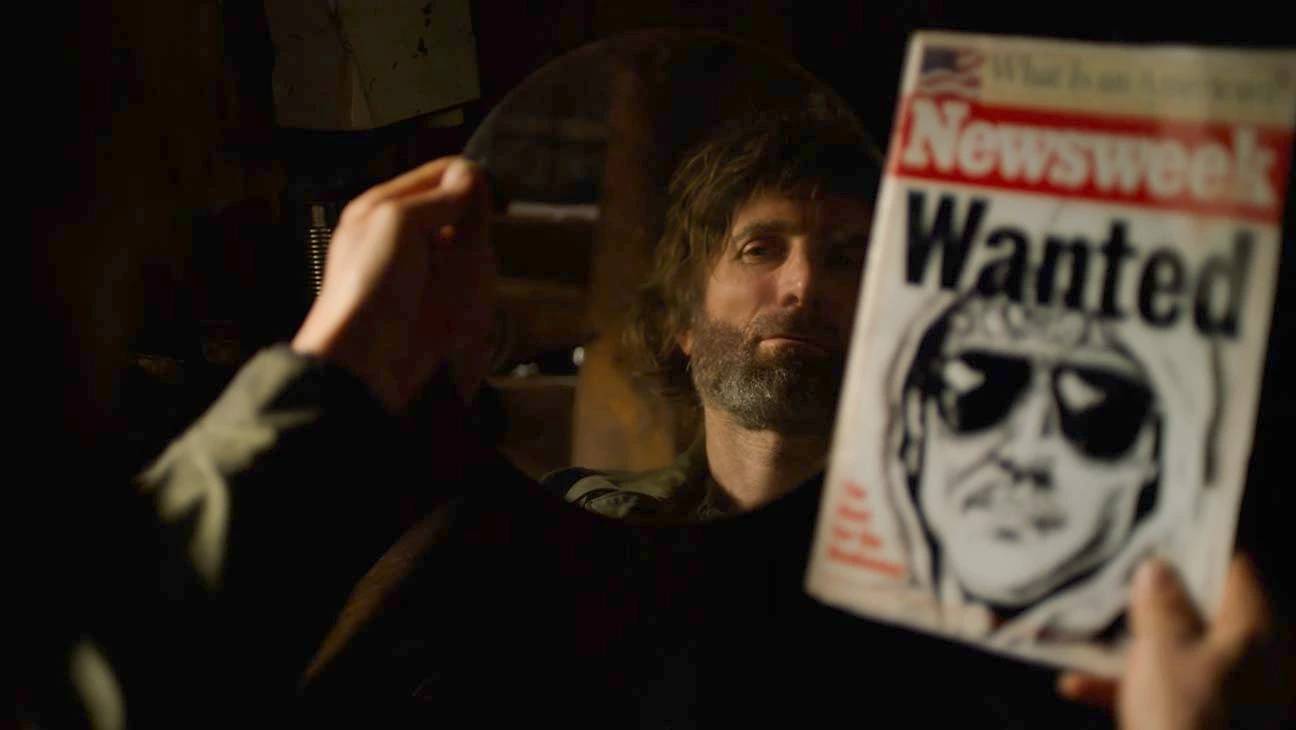

While the viewer watches Kaczynski’s observations, hears his words and sees his actions, there are moments which feel unnervingly documentary-like. Certain camera shots evoke documentaries following the likes of doomsday preppers, and there are a few moments where Copley looks directly at (and acknowledges) the camera. It catches the viewer off guard, takes them out of the fictional narrative and reminds them that unfortunately Kaczynski really did commit his crimes and sadly there have been others that have followed his example.

Kaczynski is full of contradictions, as evinced by his own beliefs. He resolved to fight the advancement of technology while using all manner of technologies himself. After all, even though he was living off the grid he still had a battery-powered radio, and when he crafted his explosive devices he would do so in motel rooms in the city with the television on. He would even seek out work with a local logging company (one of his environmental enemies) before being fired for refusing to defer to his female manager.

He would even use a payphone regularly to call his mother and brother begging for more money. It’s these phone booth conversations which provide interesting insight into the relationship he had with his mother and brother, both of which appear strained by Kaczynski’s eccentric and extreme beliefs. Ironically, the slogan posted on the Montana Telephone phone booth reads “We’re All Connected.”

In another decision which lends greater authenticity to the story, Ted K was made on the land where his cabin resided. This helps to show the type of idyll Kaczynski had been living in, the resources which were being used to further industrialisation and the natural world he was accustomed to. In spite of the ugliness of Kaczynski’s words and actions, the film manages to capture some intimate moments of beauty: a herd of deer walking single-file through the snowy landscape, their breaths visible, a rabbit foraging under the snow for a meal, a male barn owl awake in the night.

It’s a huge ask for an actor to embody someone with such extreme beliefs and behaviours, but Sharlto Copley is excellent as Kaczynski. He manages to bring Kaczynski to life in this film without making him too overtly curmudgeonly or pitiable. With some of Kaczynski’s writings it could be very easy to veer into “get off my lawn” territory, and the script and Copley’s performance avoids this.

Ted K is a unique take on the biopic genre which doesn’t seek to make a hero out of Kaczynski, but goes some way towards explaining his mindset and motivations.